Gastroenterology is a complex and vital medical specialty focused on the health of the digestive system.

This field encompasses the entire gastrointestinal (GI) tract, including the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colon, as well as the accessory organs of digestion: the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. The importance of GI care is profound, as it spans the full continuum of healthcare delivery.

Introduction to gastroenterology

In the inpatient setting, gastroenterology teams manage acute, life-threatening emergencies like upper GI bleeds, severe pancreatitis, or acute liver failure. In the outpatient clinic, they are the primary managers for a spectrum of chronic, lifelong conditions such as Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and hepatitis. Perhaps most visibly, they operate high-volume, technically demanding procedural suites for vital cancer screenings and diagnostic interventions, such as endoscopy and colonoscopy.

For facility leaders, clinicians, and operations managers, this specialty presents a unique set of challenges.

What is involved in managing a gastroenterology clinic?

It is a demanding balance of clinical complexity, high financial stakes, significant regulatory burdens, and the need for impeccable operational workflow. Prioritizing gastroenterology clinic management is not just about efficiency; it is the foundation of patient safety.

This article examines the operational frameworks, staffing models, and best practices in gastroenterology that characterize a high-performing GI service line. We will examine how best practices support quality and financial success in GI units by optimizing multidisciplinary teamwork, ensuring procedural safety, and managing the specialized staff who make it all possible.

Core gastroenterology practice models and workflows

The traditional, physician-centric model of care is rapidly becoming obsolete in high-volume specialties, such as gastroenterology. To meet the overwhelming demand for both chronic disease management and procedural screenings, modern GI practices are built on team-based models and sophisticated workflow protocols.

Team-based care models

The most successful practices utilize collaborative gastroenterology approaches that leverage every clinician to the top of their license.

The "pod" model

This common structure pairs a gastroenterologist (physician) with an advanced practice provider (APP), such as a nurse practitioner or physician assistant. In this model, the physician's schedule is heavily optimized for new patient consultations and complex procedures.

The APP's role

How do advanced practice providers support GI workflow and patient care?

APPs are the engine of clinic efficiency. They manage the long-term, stable follow-up patients (e.g., IBD in remission, chronic hepatitis C surveillance), handle post-procedure follow-up calls and visits, and triage acute patient calls. This interprofessional collaboration allows the practice to see more patients safely and effectively.

Scheduling, triage, and workflow optimization

Gastroenterology workflow optimization is a science of its own, focused on "right patient, right provider, right time."

- Intelligent scheduling: What care models optimize patient flow and clinic efficiency? Models that use "visit-type" templates. A new patient visit is scheduled for 45-60 minutes, while a stable follow-up with an APP is 20-30 minutes. Procedural scheduling (for the endoscopy suite) is done in "blocks," with procedure times varying by type (e.g., 30 minutes for a screening colonoscopy, 60+ minutes for a complex EGD with dilation).

- Nurse-led triage: A robust triage system, staffed by experienced GI nurses, is critical. These nurses use approved protocols to determine if a patient's call ("I have abdominal pain") requires an emergent ED visit, an urgent clinic appointment, or at-home advice. This protects clinic schedules from being derailed by acute issues and ensures patients are seen at the appropriate level of care.

This focus on enhancing gastroenterology patient flow is essential. By separating high-volume, stable chronic care (managed by APPs and nurses) from high-acuity diagnostic and procedural care (managed by physicians), a GI unit can significantly improve efficiency, reduce patient wait times, and increase overall capacity.

GI healthcare professionals: Roles and specialized training

A gastroenterology unit is a complex ecosystem of specialized professionals. Managing gastroenterology teams requires a deep understanding of each role, its specific skill set, and its contribution to patient safety and operational flow.

Critical staff roles in gastroenterology practice management

What staff roles are critical in gastroenterology practice management?

Gastroenterologists (physicians)

These are the clinical leaders. After completing medical school and an internal medicine residency, they typically pursue a 3- to 4-year fellowship in gastroenterology. They are the experts in diagnosis, performing complex procedures (EGD, colonoscopy, ERCP, EUS), and creating comprehensive treatment plans for chronic conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or liver failure.

Advanced practice providers (NPs/PAs)

As described above, APPs are crucial for clinic efficiency. They manage a large panel of patients, provide extensive patient education (e.g., teaching how to use a biologic injector), and often assist during procedures in the hospital setting.

GI nurses (RNs)

The GI nurse is a highly skilled, specialized role. In the clinic, they are triage experts and patient educators. In the procedural suite (endoscopy unit), they are fundamental to safety. Their duties include:

- Patient prep: Performing pre-procedure assessments, verifying consent, and establishing IV access.

- Sedation management: Administering and monitoring patients under moderate sedation (conscious sedation). This is a high-stakes role requiring ACLS certification and sharp assessment skills.

- Procedural assistance: Assisting the physician by managing biopsy specimens, controlling suction, or advancing specialized tools through the endoscope.

- Post-procedure care: Monitoring patients in the PACU (post-anesthesia care unit) or recovery bay, managing post-sedation symptoms, and providing detailed discharge instructions.

GI technicians (endoscopy techs)

Techs are the physician's "right hand" during a procedure and the unsung heroes of unit safety. They prepare the procedure room, ensure all equipment (scopes, snares, biopsy forceps) is present and functional, assist with tissue collection, and, most importantly, are responsible for the high-level disinfection and reprocessing of endoscopes.

Facility and operations managers

This is the administrative leader who orchestrates the entire service line. Their job includes staff scheduling (a complex matrix of docs, nurses, techs, and rooms), managing the credentialing process, overseeing the budget and gastroenterology billing and coding, ensuring regulatory compliance (e.g., Joint Commission, AAAHC), and managing gastroenterology equipment maintenance and procurement.

Training and certification

How is clinical staff trained for GI safety and documentation standards?

Training is rigorous and ongoing.

What certifications are needed for working in GI units?

- Nurses: Must have BLS and ACLS. The gold standard is the CGRN (Certified Gastroenterology Registered Nurse), a specialty certification that validates expertise in the field.

- Technicians: Many pursue the CFER (Certified Flexible Endoscope Reprocessor) credential or the GTS (GI Technical Specialist) certification, which are critical for demonstrating competency in equipment handling and infection control.

Staff training in gastroenterology units

is continuous. It includes regular drills for adverse events (such as a patient being over-sedated), competency checks on new equipment, and mandatory in-services on patient safety and infection control. This focus on gastroenterology continuing education is crucial for maintaining a safe and high-quality practice.

Outpatient and inpatient GI unit management

Managing a GI unit, whether it's a freestanding ambulatory surgery center (ASC) or a hospital-based department, requires a sophisticated approach to logistics, finance, and regulation. This is the core of facility management for gastroenterology.

Operational efficiency

The primary challenge in outpatient gastroenterology management is optimizing the schedule to maximize "throughput" while maintaining safety.

- Room/staff utilization: A manager's goal is to minimize "turnover time"—the time from when one patient leaves a procedure room to when the next patient enters. This requires a finely tuned workflow where the nurse is recovering the patient, the tech is reprocessing the scope, and the physician is completing documentation simultaneously.

- Telemedicine adoption: For non-procedural visits (e.g., IBD follow-up, hepatitis C medication checks, IBS management), telehealth has become a standard tool. It improves clinic efficiency, enhances gastroenterology patient flow, and increases patient satisfaction by reducing travel burdens.

Billing, coding, and compliance

Gastroenterology billing and coding is a major source of financial risk and reward.

What coding and billing practices are unique to gastroenterology?

- Screening vs. diagnostic: The primary challenge is the colonoscopy. A "screening" colonoscopy (CPT code G0121 or 45378) is a preventive service, often covered 100% by insurance. However, if a pre-cancerous polyp is found and removed during that screening, the procedure's primary purpose shifts from "diagnostic" to "therapeutic." This can change the billing codes (e.g., to 45385, "Colonoscopy with removal of polyp"), which may result in the patient being subject to a copay or deductible. Communicating this distinction to patients before the procedure is a key administrative task.

- Modifiers: Billing must be precise. Modifiers are used to denote incomplete procedures (e.g., patient prep was poor), multiple procedures (e.g., an EGD and colonoscopy on the same day), or other special circumstances.

- Documentation standards: Meticulous documentation standards are required to support the codes billed in gastroenterology. The procedure note must clearly state the indications, the findings (e.g., "polyp found at 30cm"), and the intervention ("removed via hot snare").

Accreditation

How do GI facilities achieve and maintain accreditation?

To receive reimbursement from Medicare and most private payers, GI facilities (especially ASCs) must be accredited. This is achieved through rigorous surveys from bodies like:

- The Joint Commission (TJC)

- Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC)

- American Association for Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities (AAAASF)

Achieving gastroenterology practice accreditation requires demonstrating compliance with hundreds of standards, ranging from fire safety and medication storage to core gastroenterology unit safety procedures and equipment logs. Maintaining it is an ongoing process of readiness and continuous quality improvement.

Clinical protocols, procedures, and equipment maintenance

The procedural suite is the high-tech, high-risk core of a gastroenterology practice. Operations here are governed by strict clinical protocols to ensure patient safety and the integrity of equipment.

Gastroenterology procedure protocols

Clinics perform a range of routine and advanced procedures:

- EGD (Esophagogastroduodenoscopy): A scope used to visualize the esophagus, stomach, and first part of the small intestine.

- Colonoscopy: A scope used to visualize the entire colon, primarily for cancer screening and IBD diagnosis.

- ERCP (Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography): A specialized procedure using X-rays and a scope to diagnose and treat problems in the bile and pancreatic ducts (e.g., removing gallstones).

- EUS (Endoscopic Ultrasound): A scope with an ultrasound probe on the end, used to "see" through the GI wall to stage cancers or diagnose pancreatic cysts.

- Capsule endoscopy: The patient swallows a "pill cam" that takes thousands of pictures as it travels through the small intestine, an area that is difficult to reach with traditional scopes.

Safety and equipment maintenance

What are the key safety protocols for GI procedures?

- The "time out": This is a mandatory, pre-procedure "pause" where the entire team (physician, nurse, tech) stops and verbally confirms the correct patient, correct procedure, correct site, and reviews any critical allergies or medical issues. These are core safety procedures for the gastroenterology unit.

- Sedation monitoring: This is a primary nursing responsibility. The nurse monitoring the sedated patient can have no other duties. They must track vital signs, level of consciousness, and respiratory status from the moment the medication is given until the patient is in recovery.

- Infection control: This is the most critical safety protocol in gastroenterology.

Gastroenterology equipment maintenance is closely tied to infection control.

How is equipment maintained for compliance and optimal outcomes?

The focus is on endoscope reprocessing.

Reprocessing is not "cleaning"

It is a complex, multi-step process of high-level disinfection (HLD).

The steps:

- Pre-cleaning: Manual, bedside cleaning in the procedure room immediately after use.

- Leak testing: Submerging the scope to check for microscopic holes in the casing.

- Manual cleaning: Meticulously brushing and flushing all internal channels with an enzymatic detergent.

- High-level disinfection: Placing the scope in an automated endoscope reprocessor (AER), which flushes it with a chemical disinfectant (like glutaraldehyde or peracetic acid) for a specific time and temperature.

- Drying and storage: Flushing channels with alcohol and air, then hanging the scope vertically in a clean, drying cabinet.

Failure at any of these steps can lead to patient-to-patient transmission of deadly infections. Meticulous logs of every scope, every cycle, and every technician are a legal and ethical requirement.

Technology-enabled care in gastroenterology

Technology in gastroenterology care is evolving at a breakneck pace, moving beyond simple record-keeping to actively improving clinical quality, workflow, and documentation.

How does technology improve GI workflow and documentation?

EHR integration

Modern EHRs are optimized for gastroenterology. They feature:

- Procedure note writers: Software that pulls images and data directly from the endoscope into a structured report.

- Automated recall: Systems that automatically track patients who are due for their next screening colonoscopy (in 3, 5, or 10 years) and send recall letters.

- Data tracking: Discrete data fields for gastroenterology documentation standards, such as polyp size, location, and pathology. This data is then used for quality improvement in gastroenterology units.

Telemedicine

As discussed, telehealth is ideal for non-procedural care. It enables APPs and physicians to remotely manage patients with chronic IBD, IBS, and hepatitis C, improving clinic efficiency and patient access.

Remote monitoring

For IBD patients, apps that allow them to track their symptoms, diet, and stress levels provide valuable data to the clinical team between visits.

What are the new tech trends in managing gastroenterology units?

The most significant trend is the integration of artificial intelligence (AI):

- AI-enabled polyp detection: This is the new standard. AI software works in real-time during a colonoscopy, overlaying a "box" on the screen to highlight subtle or flat polyps that the human eye might miss. This application of AI directly increases the Adenoma Detection Rate (ADR), the single most important metric for a high-quality colonoscopy.

- AI for workflow: AI algorithms are also being used to optimize complex procedure schedules, balancing staff, room, and physician availability to maximize efficiency.

Quality, safety, and performance improvement

In gastroenterology, quality is not abstract; it is quantifiable and measurable. The field is a leader in using continuous quality improvement (CQI) metrics to drive performance, ensure safety, and improve patient outcomes.

What CQI initiatives are effective in GI units?

Effective initiatives are data-driven and focus on nationally recognized benchmarks. The most important metrics for an endoscopy unit include:

- Adenoma detection rate (ADR): The "king" of all GI metrics. This is the percentage of screening colonoscopies (in patients over 50) where at least one pre-cancerous polyp (adenoma) is detected and removed. A high ADR is directly linked to a lower risk of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer.

- Withdrawal time: The amount of time the physician spends withdrawing the scope from the colon. The national benchmark is an average of at least 6 minutes. Slower, more meticulous withdrawal times are directly correlated with higher ADRs.

- Bowel prep quality: The clinic tracks the percentage of patients who arrive with an "excellent" or "good" bowel prep. Poor prep leads to missed polyps and repeat procedures, so a low-quality score triggers a review of the clinic's prep instructions.

- Complication rates: Tracking rates of perforation, post-procedure bleeding, and adverse sedation events.

Safety strategies

These metrics are supported by robust gastroenterology unit safety procedures:

- Checklists: Using pre-procedure and post-procedure checklists, similar to the aviation industry, to ensure no step is missed.

- Simulation training: Running "mock codes" or simulation drills for rare but dangerous events like a perforation, a severe allergic reaction to sedation, or a fire in the procedure room.

- Interprofessional audits: How do multidisciplinary audits improve GI safety and outcomes? This is a core component of multidisciplinary gastroenterology care. A team (e.g., a nurse, a tech, and a physician) will periodically audit their peers. They might review charts to check documentation, observe the "time out" process to ensure compliance, or audit the scope reprocessing logs. This non-punitive, peer-to-peer feedback is a powerful driver for quality improvement in gastroenterology units.

Multidisciplinary collaboration and care coordination

Gastroenterology does not exist in a silo. Digestive and liver diseases are systemic, requiring comprehensive, multidisciplinary gastroenterology care and coordination with a wide range of other specialties.

How do teams coordinate complex GI care?

They use collaborative gastroenterology approaches and structured communication.

What multidisciplinary approaches improve outcomes for chronic or high-risk patients?

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

An IBD patient may be co-managed by:

- GI: Manages the primary disease and medications.

- Colorectal surgery: For cases requiring bowel resection or ostomy.

- Rheumatology: To manage the common "extra-intestinal manifestations" like inflammatory arthritis.

- Dermatology: For related skin conditions.

- Dietitian: For managing nutrition during flares.

Gastrointestinal cancers (e.g., colorectal, pancreatic)

All new cancer diagnoses are discussed at a multidisciplinary "tumor board." This is a formal meeting including the gastroenterologist, surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, and radiologist to create a consensus treatment plan.

Chronic liver disease

A patient with cirrhosis is managed by GI/hepatology, a dietitian (for low-sodium diets), interventional radiology (for TIPS procedures), and a case manager or social worker to coordinate care and address factors like alcoholism or hepatitis C treatment access.

These collaborations are managed through shared EHR documentation, regular case conferences, and dedicated nurse navigators who act as the central point of communication, guiding the patient through these complex transitions between specialties.

Flexible workforce and contingent staffing in GI units

One of the greatest challenges in managing a gastroenterology clinic is staffing. The procedural units are high-stakes environments that cannot operate unsafely. A single sick call from an experienced sedation nurse can cancel an entire physician's block of procedures, resulting in a massive backlog and significant revenue loss.

At the same time, GI volume is notoriously variable. It can be impacted by physician vacations, seasonal lulls, or changes to insurance plans at the start of the year. This makes a flexible, "core-and-flex" staffing model essential.

How do flexible staffing platforms support GI operations and safety?

- Bridging the gap: A manager can maintain a lean, efficient core team and use gastroenterology staffing platforms to fill in the gaps. This allows the facility to adapt to a 20% drop in volume (e.g., a doc is on vacation) or a 20% increase in volume (e.g., covering a surge) without being over- or under-staffed.

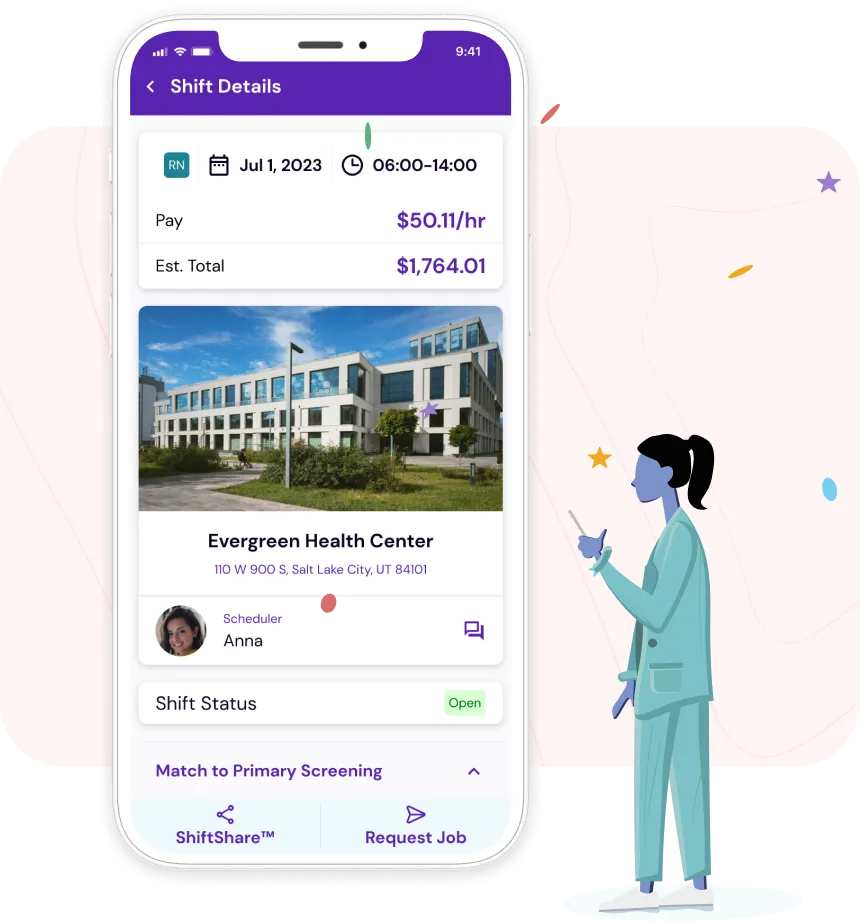

- Specialized skill access: Finding experienced GI nurses can be challenging. A tech-enabled solution like the Nursa clinician marketplace allows a manager to post PRN gastroenterology jobs and specifically request clinicians with "GI," "Endoscopy," or "CGRN" experience. This ensures they are getting a competent, qualified professional.

- Immediate coverage: When a core nurse calls in sick at 5 AM, a manager can't wait days for an agency. They can post the shift on the Nursa clinician marketplace and often have it filled by a local, credentialed clinician within minutes, saving the day's procedure list. This flexible model is key to operational resilience.

What onboarding protocols ensure quality with contingent staff?

Bringing in PRN staff safely requires a "rapid onboarding" checklist. The PRN clinician, whose credentials have already been verified by the platform, arrives and is given a 15-minute unit orientation:

- "Here is the crash cart."

- "This is our 'time out' protocol."

- "This is our documentation system."

- "These are the sedatives we use." This ensures that contingent staff can integrate safely and immediately contribute, preventing the burnout and staffing crises that plague so many healthcare units.

Research, education, and future trends in gastroenterology

The field of gastroenterology is at the forefront of medical innovation. The latest research in gastroenterology is not just iterative; it's revolutionary, and these trends will shape facility operations and clinical practice for years to come.

What are the newest research priorities in gastroenterology operations?

- The microbiome: This is the single biggest area of research. We are just beginning to understand how the trillions of bacteria in our gut (the microbiome) influence health. This research is leading to new therapies like Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) for C. difficile and new insights into the causes of IBD, obesity, and even mental health.

- Non-invasive diagnostics: The "holy grail" is a blood test or stool test that can reliably detect colorectal cancer and advanced polyps. These "liquid biopsies" could one day supplement or, in some cases, replace the need for invasive, expensive colonoscopies for average-risk patients.

- Advanced therapeutics: The field is moving beyond just "looking." Endoscopists are now performing procedures that were once reserved for surgery, such as endoscopic suturing, tumor removal (endoscopic submucosal dissection), and bariatric (weight-loss) procedures, all of which are done entirely through a scope.

How can facilities and clinicians prepare for future trends?

The key is a commitment to gastroenterology continuing education:

- For clinicians: This means pursuing advanced certifications like the CGRN, attending national conferences, and learning the new technologies (like AI-assisted scopes) as they are introduced.

- For facilities: This means investing in new technology in gastroenterology care, budgeting for staff training, and fostering a culture of quality improvement in gastroenterology units.

The future of gastroenterology will be less invasive, more data-driven, and highly personalized. It will require facilities and teams that are not only clinically excellent but also operationally nimble and technologically fluent.